Back in 2011 many pendency metrics were at or near all time highs. It typically took 2 or 3 years just to got a first office action. For a startup, those delays could have huge ramifications on whether and at what price it could get funded. To them, the arrival of the track 1 prioritized examination program seemed like nothing short of a miracle. (True, it also felt like extortion, but that’s getting off topic…)

Between 2011 and 2014 I worked on a lot of Track 1 applications. These were primarily for startups and growth stage companies that needed patents ASAP. But as we saw more and more allowances and well-reasoned rejections roll in under the program, we started to wonder: was it just coincidence, or were track 1 applications actually getting more favorable treatment and/or better examiners? Today I finally got around to attempting to answer that question.

Note: The tables below look at various metrics for track 1 applications where the request was filed with the application (i.e., it excludes Track 1 applications where the request was filed with an RCE). Also, for “standard” track applications I have excluded applications which have been made special for any reason.

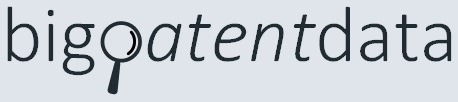

Track 1 applications are about 1 year faster to “final” disposition

The above shows the time from the application being placed on the examiner’s docket until the first final rejection, allowance, or abandonment (“final” disposition). Ignoring 2011 and 2012 (because there had not been much time for many final dispositions by then), Track 1 applications have pretty consistently taken around 200 days to reach final disposition.

Important to note here is that I started the clock at the time the application was placed on the examiner’s docket, rather than its filing date. I did this to account for most (but not all) delays that fall at the feet of the applicant — typically in the form of notices of missing parts, notices to file corrected application parts, and other pre-exam formalities notices. (Aside: There were a surprising number of Track 1 applications where the applicant/attorney took months – sometimes years – to get the application in condition for examination. Why pay track 1 fees and then take 2 months to respond to a notice of missing parts!?)

Why pay track 1 fees and then take 2 months to respond to a notice of missing parts!?

The error bars shown represent one standard deviation. As you can see, there has been a fair amount of overlap in the past 3+ years. Very roughly, the slowest 15% of track 1 applications take longer than the fastest 15% of standard applications.1

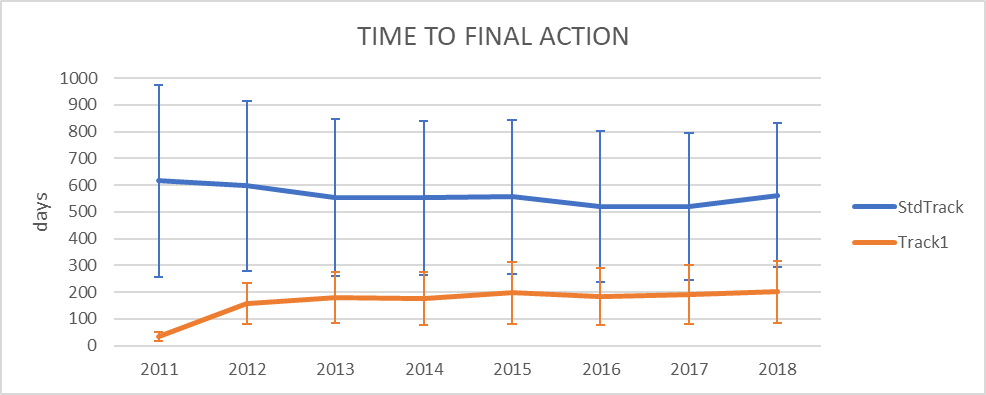

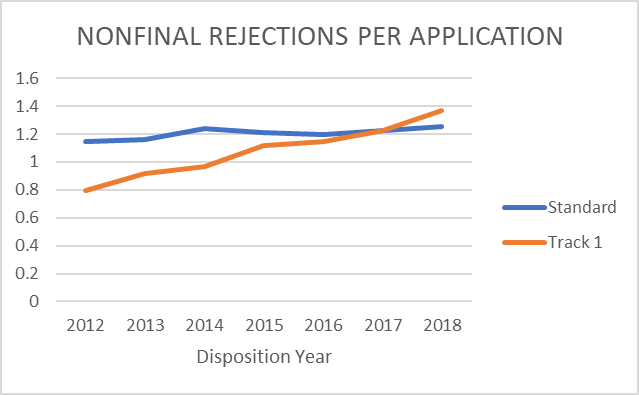

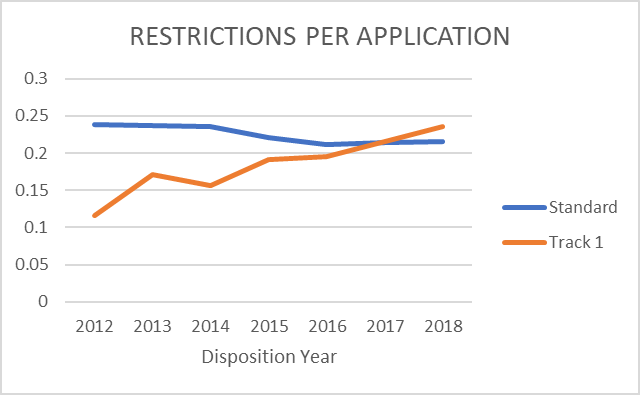

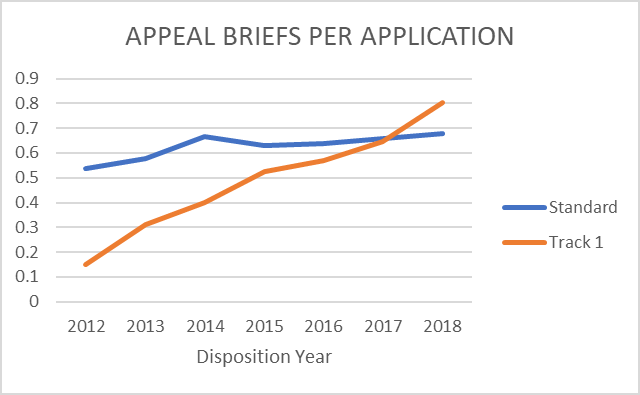

Track 1 applications receive more office actions, restrictions, and appeal briefs

I previously reported (here) that Track 1 applications now receive more office actions than standard track applications. What I didn’t show then, but do above, is the trend over time.

I also previously mentioned (here), that I feel like majority of restrictions are questionable at best (at least in the electronic arts where I focus). Some small part of me hoped that paying the Track 1 “vig” would reduce nitpicky (or just plain wrong) restrictions. This chart indicates otherwise.

The steady rise in these metrics for track 1 applications is likely a simple function of time. As track 1 applications with longer/more difficult prosecution have wound their way through the PTO, the per-application averages have risen. In other words, the values for previous years were artificially low due to the immaturity of the program. In fact, given the steep slopes, it appears that the track 1 metrics will settle significantly higher than the standard track. I think this makes sense if you assume applicants are reserving track 1 (and its higher costs) for “more important” applications for which they are willing to fight harder.

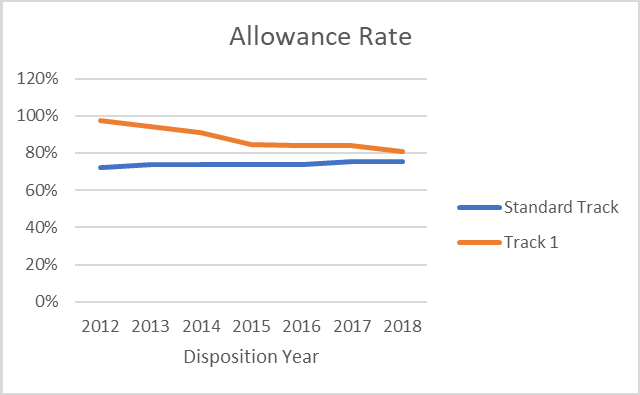

The allowance rate of Track 1 applications is converging with standard track applications

Again, I think this is just a simple function of time. Abandonments typically take much longer than allowances. As the abandonments continue to work their way through the system, the allowance rates should converge.

Sometimes “experience” just means “small sample size”

Due to past successes with track 1 applications, I was under the impression that track 1 applications received more favorable treatment at the PTO. The above data suggests that not to be the case.

This goes gets to the heart of what I am trying to accomplish with BigPatentData and this blog. Questions like: “Do Track 1 applications get more-favorable treatment?” have objective answers. But because we do not have the data to answer such questions, we are forced to rely on our “experience” (which, in this context, amounts to a very small data set). In this example my past experience may lead me to a conclusion not supported by the broader data.

Experience is critical for answering all the questions we face everyday that do not have clear cut answers. But for questions that have objectively-measurable answers, we should be using the wider pool of data that is now becoming available. In this case, the data shows that decisions about whether or not to file track 1 should not be based on the perceived quality of examination under track 1. Rather, whether to file Track 1 should be based only on speed. If you need speedy examination, then Track 1 (on average) is your best bet to get it.2

1If I was a betting man, I would bet most of the fastest standard track applications are continuations…a topic of a future post.

2Again, possibly with the exception of continuations.

Pingback:Patent Riffs & Links for Sep 11, 2018